I’ve written probably thousands of stories and articles that have been published, starting with my days at the Call-Chronicle Newspapers in Allentown, PA, when I was first married to my wife, Lynn, of 57 years. Articles published more recently included stories on the web written while working with American Baptist Churches USA and also writing for Living Lutheran, the periodical of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Writers can produce pieces and not get any feedback from them. I think hearing back from readers personally may take place more easily in local reporting. I am not sure.

I’ll relate two occasions when I did get feedback. One occasion was beyond amusing. The second one I’ll characterize as a remarkable outcome I learned about quite by chance.

When I was a young reporter, Lynn and I moved from a walkup apartment to our first house, a small Cape Cod-style dwelling in a village called Lanark outside of Allentown. The garage needed a new roof. Being of modest means, we enlisted two friends to help me put new green shingles on the roof over the old shingles. We had two wives helping by handing shingles up to us. Much to my surprise when we drove past the house quite a few years later well after we had moved away the shingles we had installed seemed to still be in place. That amazed me.

Some drinking was involved during this do-it-yourself initiative bordering at times on debacle. In short, I described a litany of mistakes we made during the effort in a self-effacing humor piece I wrote for Allentown’s Evening Chronicle. The city editor seemed to welcome these pathetic tales, such as when I tried to go through a window after locking myself out of the house. They ran with cartoons by a noted illustrator named Bud Tamblyn. The roofing piece was the first of its kind the paper had published. Readers seemed to enjoy these stories written at my own expense, perhaps because the news, even then, could be — humorless.

Bud Tamblyn’s cartoon shows the hapless roofer, right. Helping is Paul Lowe.

The next day a phone call was referred to me from the city desk. The caller identified himself as the head of the Roofers Union in the county.

“I want to thank you,” he said. “That story was the best advertisement for skilled, professional roofers the paper could have carried.” Then he concluded, “Is there any chance the story could run again next week?” I was laughing at my own expense. I had to tell him we don’t run stories like that twice.

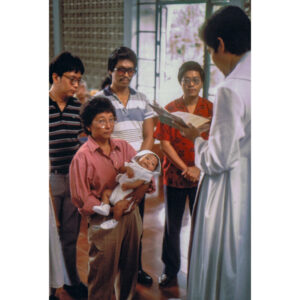

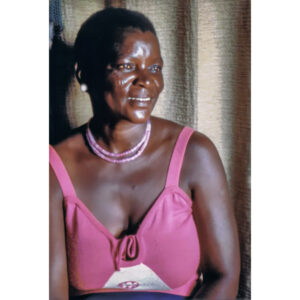

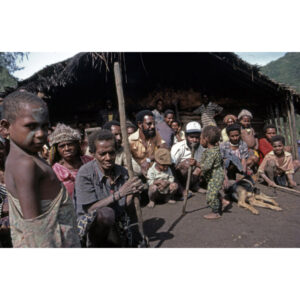

The truly unimaginable story result happened after I wrote a piece about how newly independent Zimbabwe was recovering after a horrible war. I was on assignment for The Lutheran, magazine of the denomination known then as the Lutheran Church in America. I had never done reporting and photography out of a war zone and haven’t been to such a place since. It was 1981. I wrote how children had not been able to go to school for five years. Many schools and churches had been reduced to rubble from the conflict. The Lutheran World Federation was assisting in the rebuilding and recovery. But the truth was Zimbabwe simply had not enough classrooms, not enough books, not enough teachers and too many children wandering from place to place to find a school they could register to attend. Some children had been to four places or more, always rejected. But the sense of resilience and determination in the newly peaceful young nation was palpable.

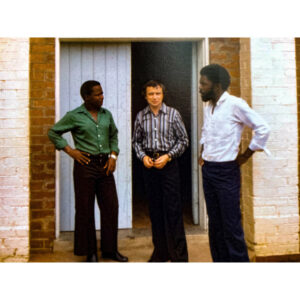

Mike Neville, center, with Zimbabwe teaching colleagues in 1981.

After the story appeared in The Lutheran (circulation nearly 300,000), I took a train from Philadelphia to New York City for a meeting. During the trip a colleague introduced me to a couple she knew, Gail Altman and Fred Noll, both teachers from downtown Philadelphia. Fred and Gail told me they were glad to meet me. They had read my story and been deeply moved by it. Now they were on their way to the church’s national headquarters to receive training to devote a year of their lives teaching children in a little Zimbabwe town called Masase that I had written about. I was flabbergasted and deeply thankful that God had empowered me to write a story producing such a result. It was truly a remarkable outcome.