I have been blessed to work as a photojournalist in a dozen countries and 30 U.S. states. Memories abound.

For example, in anticipation of the 400th anniversary of the Augsburg Confession I visited more than a dozen sites connected with the life of Reformer Martin Luther. I crossed from West Germany to East Germany in an experience that was especially emotional.

But one day in my journalistic life stands out — so much so that I think of it almost every day. It was a pivotal factor in deciding to write my book Neighbors Revisited, a church journalist’s life lessons learned from people of other cultures.

It was the 22-hour period of time when I visited a village in Papua New Guinea called Nomane in that young nation’s Central Highlands.

We live in a highly transactional culture. For example, when I used to visit a drugstore to purchase shampoo (I don’t need it anymore), I would pick up what I wanted and, often in a preoccupied state, pay for it at the checkout counter while barely noticing the cashier.

On the Papua New Guinea day in question in 1985, burdened with a heavy camera bag to take black and white color photos, I flew with a mail plane pilot in a single engine Cessna to Nomane, landing on the side of a majestic peak on a muddy airstrip.

I had plotted out my schedule over 22 hours ahead, some of which would be spent sleeping (hopefully). As a deadline-oriented writer I wanted to get a jump start, meeting the village evangelist Manape Nokul and telling the story about how, counter-culturally, he had persuaded his neighbors to move their village from high terrain (where you could be more protected from your enemies) to lower, more fertile ground especially suited for farming. I learned from a pastor who grew up in Papua New Guinea that moving was a special problem because villagers feared spirits that they believed would hang out near the river they were moving toward. In the book I titled this chapter “How faith moved a village and how a village moved me.” Years later the title still seems especially fitting.

I quickly learned from the German missionary who hosted me that jump-starts wouldn’t work in the village. “You have to spend time with the leaders first. You have to have a meal with them and let them ask you questions,” Phillip Hauenstein explained. (“But that will take so much time,”) I said to myself.

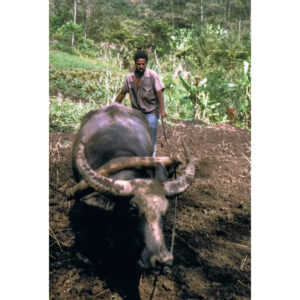

But I yielded. I ate meal of tinfish, as they called it (tuna in a can, a delicacy saved for feasts) and baked potato. The questions to me poured forth. “Where did you come from? How did you get here? What is your home like? Are there farmers where you live? What is your family like? What do you think of our village?” Around 11 p.m. the questions and answers ended. Except for one. “What would you like to do here?” they asked. I said I wanted to meet and talk to Manape. I wanted him to tell me the story of the village and talk about the faith of the villagers. I wanted to take lots of pictures. I knew they had just started farming with a water buffalo. They had only had metal tools for 40 years. Especially, I said, I would like to take a photo of the villagers together.Would all of this be OK? I asked. They all nodded.

Phillip and I said our good-byes and headed off for bed in his bungalow. It began to rain — very hard. I thought that the persistent rain might wreck my plans for the next morning. “Don’t worry,” Phillip told me. “It often rains here at night. It will be a beautiful day tomorrow.” I listened to the rainfall on the bungalow roof as I tried to sleep — fretting.

As Phillip predicted. the next morning dawned with a clear sky. We made our way to the village.

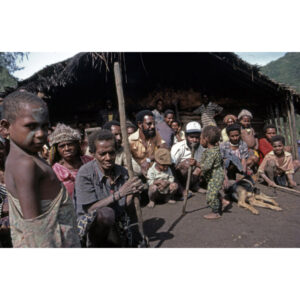

No-one was there. I panicked. What is happening? “I think I know,” Phillip mused. “Follow me.” We walked up a curvy ribbon dirt trail to the top of the village. There, positioned perfectly for a photo before a picturesque hut were all the villagers. Dear friend, you have probably taken photos where you have to arrange the subjects suitably, move them closer together, tall ones in the back etc. Especially if you are photographing a lot of people.

I needed to do nothing of the sort. They had listened to me so carefully. Everything was perfect. I took out my cameras and began to shoot. I had tears in my eyes.

The whole day went like that. The additional pictures took half the time they would have because the villagers had planned for me. Manape’s interview worked efficiently because he had heard my questions the night before.

These villagers some would describe as “primitive” were not at all transactional. Because they had come to know me so well first my assignment was easily and completely fulfilled. I had learned a special lesson about hospitality and the embracing of a total stranger. The experience changed me.

As I said good-bye to the village at 2 p.m., boarding the Cessna once more, I found myself asking “Who are the primitive people anyhow?”

Manape plowing with a water buffalo.

The villagers were positioned perfectly for a photo.

Leave a Comment